This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Sampling Distribtution, 표본분포

Sample Distribution (표본분포)과 Sampling Distribution (표집분포)는 비록 비슷하게 들리겠지만 전혀 다른 의미를 갖는다. 전자는 하나의 샘플에서 추출한 구성원에 대한 분포를 말한 것이고, 후자는 여러개의 샘플들의 평균에 대한 분포를 말하는 것이다. 공통적인 점이 있다면 둘 다 모집단에 (population) 대한 샘플을 (sample) 의미한다는 것 – 즉, 모집단의 특성을 (parameter) 추측 (inferring) 하기 위해서 구해진 집단이라는 것이다.

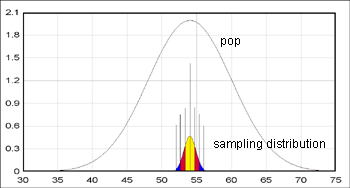

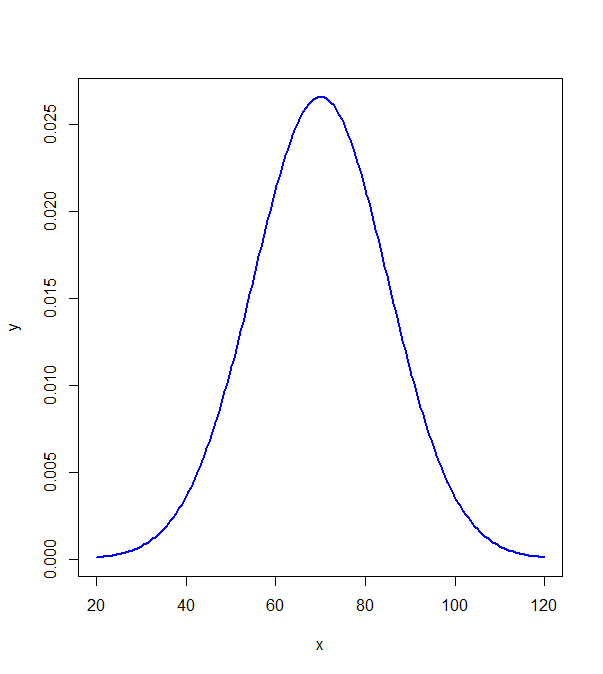

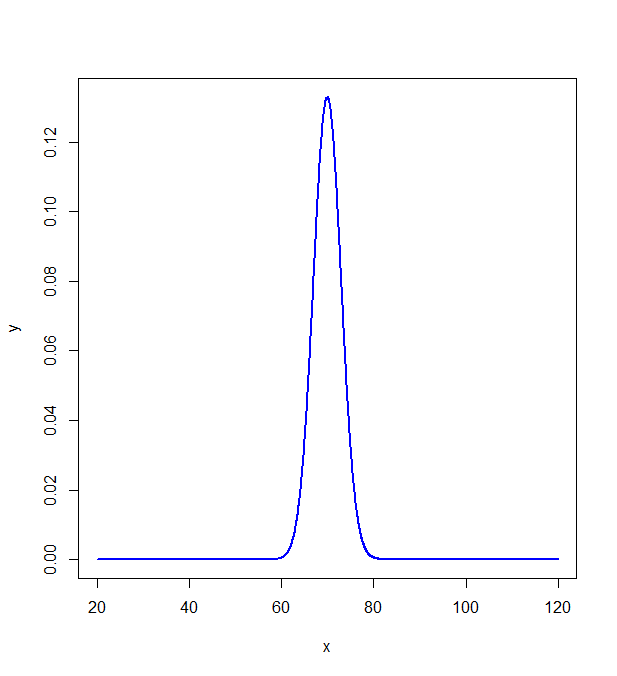

Fig. 1: population m=70 sd=15 Sample distribution이 population의 parameter와 동일한 statistics을 가질 확률은 그리 많지 않다. 가령, 우리나라 대학생의 communication apprehension 지수가 (index) 70이고 standard deviation이 15라고 가정하면, 연구자가 하나의 샘플을 뽑았을 때, 그 샘플의 Mean과 standard deviation이 population의 그것과 동일할 확률은 그리 크지 않을 것이다. 따라서 연구자는 Probability Sampling 방법을 통해서 모집단과 최대한 유사한 샘플을 뽑으려고 할 것이다. 그럼에도 불구하고 샘플의 평균은 모집단의 평균보다 클 수도 혹은 작을 수도 있다1).

Fig. 1: population m=70 sd=15 Sample distribution이 population의 parameter와 동일한 statistics을 가질 확률은 그리 많지 않다. 가령, 우리나라 대학생의 communication apprehension 지수가 (index) 70이고 standard deviation이 15라고 가정하면, 연구자가 하나의 샘플을 뽑았을 때, 그 샘플의 Mean과 standard deviation이 population의 그것과 동일할 확률은 그리 크지 않을 것이다. 따라서 연구자는 Probability Sampling 방법을 통해서 모집단과 최대한 유사한 샘플을 뽑으려고 할 것이다. 그럼에도 불구하고 샘플의 평균은 모집단의 평균보다 클 수도 혹은 작을 수도 있다1).

위의 모집단은 $\mu=70, \;\; \sigma=15$ 의 특징을 갖는다. 이 모집단을 가지고 아래와 같은 가상의 실험을 한다고 생각해보자.

n = population의 숫자 인 case

이 모집단에서:

- 샘플 구성원의 숫자가 N인 샘플 (sample size, n=N) 을 뽑아서 평균을 기록하고

- 다시 그 샘플을 모집단에 넣은 다음

- 다시 샘플을 (n=N) 뽑아 그 평균을 기록하고,

- 다시 모집단에 귀속시키고 . . . .

의 절차를 끝없이 (상상으로) 반복하여 그 평균값들의 분포를 (distribution of the sample means) 그린다면 어떻게 될까?

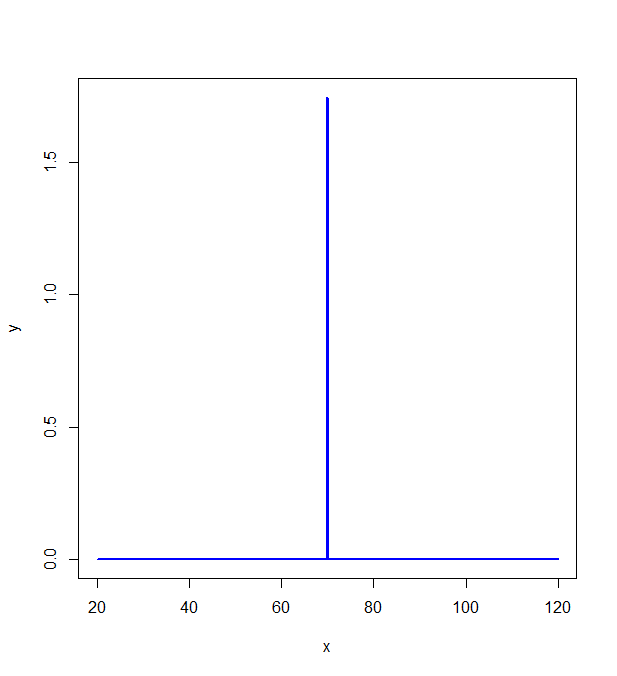

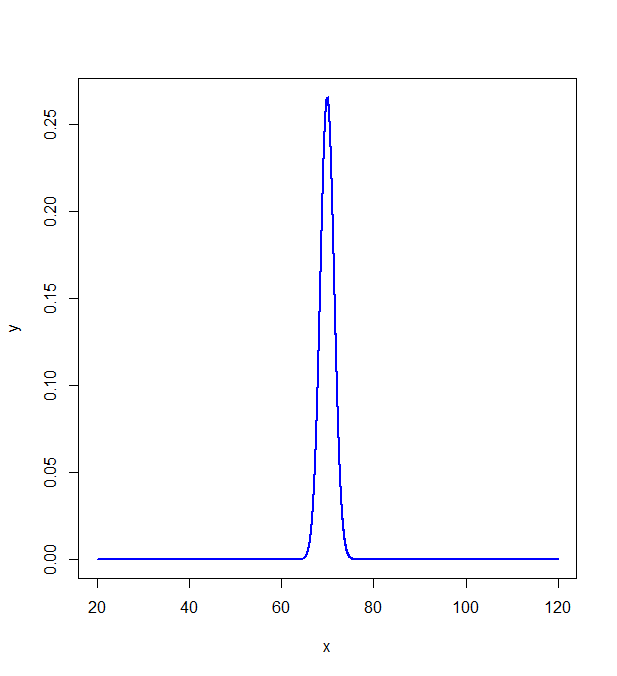

Fig. 2: sampling distribution n=population 위의 실험은 영락없이 우습게 들릴 수 있다. 왜냐하면, 모집단 전체의 구성원을 조사한다면, 그 모집단의 평균만이 계속 나오기 때문이다. 즉, 위의 방법에서 구한 평균값들의 집단은 모두 단일한 값인 70을 갖게 된다. 그렇다면, 이 평균들의 집단의 표준편차 즉 standard deviation값은 어떨까? 이 값은 0을 갖게 된다.

Fig. 2: sampling distribution n=population 위의 실험은 영락없이 우습게 들릴 수 있다. 왜냐하면, 모집단 전체의 구성원을 조사한다면, 그 모집단의 평균만이 계속 나오기 때문이다. 즉, 위의 방법에서 구한 평균값들의 집단은 모두 단일한 값인 70을 갖게 된다. 그렇다면, 이 평균들의 집단의 표준편차 즉 standard deviation값은 어떨까? 이 값은 0을 갖게 된다.

연구자는 위의 사실에서 다른 사람들에게 다음과 같이 이야기 할 수 있다. “만약에 당신이 N으로 이루어진 샘플을 뽑아서 평균을 낸다면, 그 평균값은 70일 확율이 100%입니다”. 이와 같이 샘플들의 평균을 모아서 분포곡선을 그려보면, 그 샘플의 평균이 어떻게 나올 것인가를 알 수 있는 방법이 있게 된다.

그렇다면, 만약에 n=1 인 경우의 샘플 평균들의 분포곡선은 어떤 성질을 가질까?

n = 1 인 경우

이 모집단에서:

- 샘플 구성원의 숫자가 1 인 샘플 (sample size, n=1) 을 뽑아서 평균을 기록하고

- 다시 그 샘플을 모집단에 넣은 다음

- 다시 샘플을 (n=1) 뽑아 그 평균을 기록하고,

- 다시 모집단에 귀속시키고 . . . .

의 절차를 끝없이 (상상으로) 반복하여 그 평균값들의 분포를 (distribution of the sample means) 그린다면 어떻게 될까?

위의 샘플평균들의 분포는 모집단 평균을 평균으로 하게된다. 또한 모집단의 최소값과 최대값은 샘플 평균들의 분포에서 각각 최소값과 최대값으로 나타나게 된다. 따라서 연구자는 사람들에게 다음과 같이 이야기할 수 있다. “만약에 당신이 n=1인 샘플을 뽑는다면, 그 샘플의 평균(그 샘플의 값이 될 것이다)이 나올 수 있는 범위는 population의 최소값에서 population의 최대값일 것이다”. 이 범위가 정확히 어디서 시작하고 끝나는지는 위에서 알려진 정보로는 알 수 없지만 (평균=70, 표준편차=15 만 알려져 있을 뿐, 최소값과 최대값은 모르는 상태), 샘플을 취했을 때 그 샘플의 평균이 어느 범위에서 나오는가는 추측할 수 있다.

그렇다면 n = 4로 하여 샘플을 뽑는 경우는 어떨까?

n = 4 인 경우

이 모집단에서:

- 샘플 구성원의 숫자가 4 인 샘플 (sample size, n = 4) 을 뽑아서 평균을 기록하고

- 다시 그 샘플을 모집단에 넣은 다음

- 다시 샘플을 (n = 4) 뽑아 그 평균을 기록하고,

- 다시 모집단에 귀속시키고 . . . .

의 절차를 끝없이 (상상으로) 반복하여 그 평균값들의 분포를 (distribution of the sample means) 그린다면 어떻게 될까?

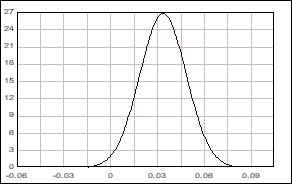

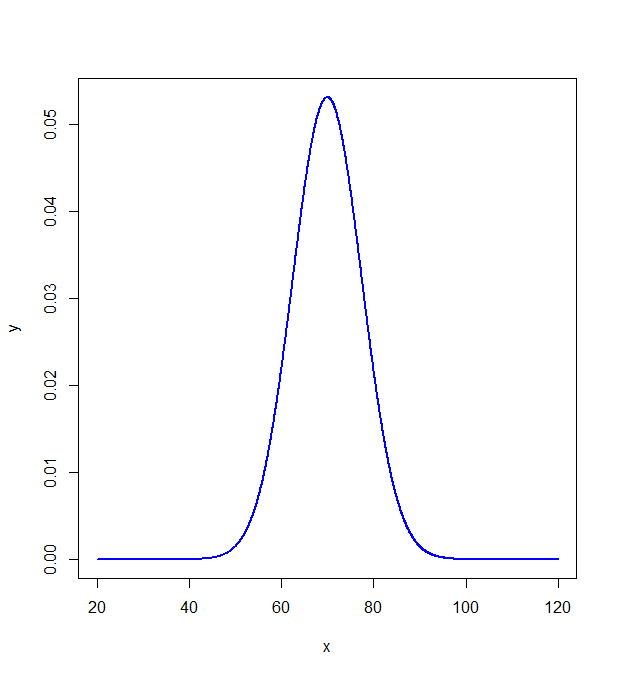

Fig. 3: sampling distribution n=4일 경우, m=70 sd=7.5 위의 경우가 n =1 인 경우와 다른 점은 샘플의 숫자이다 (n=4). n =4인 경우에 구하는 샘플의 평균값으로 나올 수 있는 최소의 값을 n = 1인 경우에 구할 수 있는 최소값과 비교하여 보자. 어떤 점수가 더 크게 나올 가능성이 많을까? 당연히 n = 4인 경우이다. n = 4인 경우에서 샘플의 평균이 n =1 인 경우의 최소값과 같기 위해서는 population의 최소값이 연속해서 4번 뽑혀야 하기때문이다. 이는 한 번만 뽑히는 경우보다 확률적으로 더 어렵다. 따라서, n = 4인 경우의 샘플평균들의 분포곡선의 최소값은 n = 1인 경우의 그것에 비하면 상대적으로 홀쭉한 모양을 갖게 될 것이다. 홀쭉하다 함은 즉 이 샘플평균 분포곡선의 표준편차는 n =1인 경우의 그것에 비하면 작다는 것을 의미한다.

Fig. 3: sampling distribution n=4일 경우, m=70 sd=7.5 위의 경우가 n =1 인 경우와 다른 점은 샘플의 숫자이다 (n=4). n =4인 경우에 구하는 샘플의 평균값으로 나올 수 있는 최소의 값을 n = 1인 경우에 구할 수 있는 최소값과 비교하여 보자. 어떤 점수가 더 크게 나올 가능성이 많을까? 당연히 n = 4인 경우이다. n = 4인 경우에서 샘플의 평균이 n =1 인 경우의 최소값과 같기 위해서는 population의 최소값이 연속해서 4번 뽑혀야 하기때문이다. 이는 한 번만 뽑히는 경우보다 확률적으로 더 어렵다. 따라서, n = 4인 경우의 샘플평균들의 분포곡선의 최소값은 n = 1인 경우의 그것에 비하면 상대적으로 홀쭉한 모양을 갖게 될 것이다. 홀쭉하다 함은 즉 이 샘플평균 분포곡선의 표준편차는 n =1인 경우의 그것에 비하면 작다는 것을 의미한다.

그렇다면 n = 16일 경우에는 어떨까?

Fig. 4: sampling distribution n=25일 경우, m=70, sd=3

Fig. 4: sampling distribution n=25일 경우, m=70, sd=3

- n = 25인 경우는?

- n = 36인 경우는?

- n = 100인 경우?

- n = 400인 경우?

- n = 900인 경우?

- n = 1600인 경우?

CLT

위에서 언급한 가상의 샘플평균들의 분포를 구한다면 그 분포곡선은 아래의 성질을 갖게 된다.

- $\mu_{\overline{\tiny{X}}} = \mu$

- $\sigma_{\overline{X}} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}$

(sampling distribution은 [Central Limit Theorem] 을 이해하기 위해서 꼭 필요한 개념이다.)

$\mu=70$ 이며 $\sigma=15$ 인 모집단의 경우에서 n = 100인 샘플을 뽑는다고 가정을 해보면,

$\mu=70$ 이며 $\sigma=15$ 인 모집단의 경우에서 n = 100인 샘플을 뽑는다고 가정을 해보면,

- $\mu_{\tiny\overline{X}} = \mu = 70$

- $\sigma_{\tiny\overline{X}} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} = \frac{15}{\sqrt{100}} = 1.5$

English

I mentioned in the earlier article that the standard error is actually standard deviation of sampling distribution. I would feel safe when I say standard deviation since I covered the concept already. However, I thought you might feel uneasy about “sampling distribution,” which may lead you all to a confusion in understanding standard error concept. If so, the article was not good enough. But, I mention about the concept (sampling distribution) implicitly without providing the definitions. So, I want to talk more about the concepts of “central tendency,” “sampling distribution” and “standard error.”

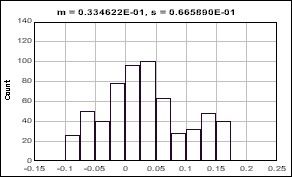

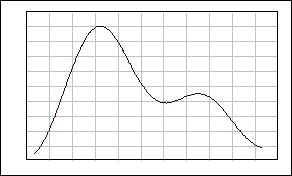

Do you remember you heard something like “no matter how the population is distributed, the statistics from the infinite numbers of samples will have normal distribution characteristics?” Suppose that the below graph show how a population is distributed (The first one is histogram, the second is distribution graph).

Certainly, you see that the distribution is not normal.

Now suppose that you took a sample from this population and recorded the mean of the sample. And suppose that you kept doing this about 1000 times. How do you think the curve of the graph look a like? Remember that you kept the means of the 10000 samples. The graph looks like the below – normally distributed curve. Again, this is obtained from numerous numbers of sample means – this is not about the sample itself.

This can be called normal curve of mean (x bar). And this distribution is called sampling distribution because the distribution graph is obtained by keeping sampling for a very very large number of times. Weiss and Leets (1998) say “[T]he sampling distribution is a theoretical distribution that is a fundamental basis for inferential statistics” (p.71).

This sampling distribution has several interesting characteristics:

$ \mu_{\overline{x}}=\mu $

$ \sigma_{\overline{x}}=\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} $ ,

We all know what the sign means, the symbols are $\mu$ and $\sigma$ in Greek, representing “mean” and “standard deviation.” The subscribed letter is for identification – who's the owner of the Greek characters? That is, The first one is mean of means (x bar), the second one is standard deviation of sampling means, (x bar). So, we can interpret them as: (1) The mean of sampling distribution is about the same as that of population. (2) The standard deviation of sampling distribution is about “standard deviation of the population/square root of sample size.”

The second is also called “standard error of the mean.” Oops, it is been covered in previous writing, but was different from this one… We are talking about sampling distribution of mean, not sampling distribution of probability. They are same thing, but obtained via different methods (they share the same idea, though).

For the reference, the standard deviation of sampling distribution of probability was,

$\sigma_{\overline{p}}=\sqrt{\frac{p*q}{n}}$

As you see, they share the same Greek letter, $\sigma$ , “standard deviation.” Strangely, they are called the standard error of the mean or the standard error of the probability.

What is this used for? At the bottom line, this is very important to do any kind of statistical (inferential) analysis. Illustration of this idea requires us to expand our thoughts a bit more, however. This is directly related to the t-test and z-test (Therefore, I strongly recommend to read “z” score section in the textbook). I will save this kind of example for the next writing.

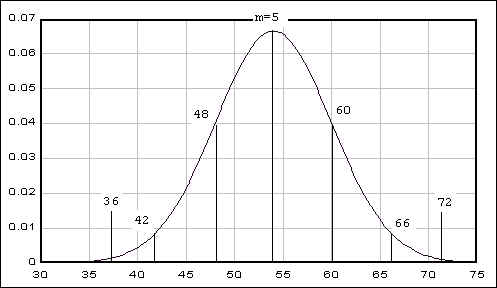

Instead, I want to talk about an example which is related to the exact above concept. Suppose that you are a member of a consumer group. The director called you – since you have taken statistics and media research course at Rutgers – and asked you to test a brand of battery. She wanted to know whether the battery life, which the manufacturer has announced to the public, holds the truth. The manufacturer has claimed that the lengths of life of its best battery has a mean of 54 months and a standard deviation of 6 months. The director told you to send a sample of 50 of the batteries.

Immediately, you draw a picture in your mind even before you get the sample set:

You are expecting that the picture represents the entire population of the batteries: their mean is about 54; about 68% of the batteries will last long between 48-60 months; 42-66 months for the 95%; 36-72 months for the 99%. And you are expecting this claim holds the truths.

You can also imagine how the sampling distribution – again, the ones from the means obtained from imaginary sampling – should look like based on the information. First, you know that the mean of means (the mean of the sampling distribution of means) is the same as that of the population. And the standard deviation of the sampling distribution is standard deviation of population divided by square root of sample size. That is,

$ \sigma_{\overline{x}}=\sigma $ , which is known as 54, and

$ \sigma_{\overline{x}}=\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}=\frac{6}{\sqrt{50}} $ , which is about 0.85 month.

These two again gives you a picture of sampling distribution. which will look like the below graph.

The inner distribution line is “sampling distribution of means” line, which shares the same mean and different (narrow – always the case) standard deviation (0.85, in this case). The ranges of the corresponding standard deviation unit is:

| | minimum | maximum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (+-) 1s (68%) | 53.15 | 54.85 | yellow | ||

| mean (+-) 2s (95%) | 52.3 | 55.7 | yellow | red | |

| mean (+-) 3s (99%) | 51.45 | 56.55 | yellow | red | blue |

sample score. Now, suppose that the mean of you particular sample set (n=50) turned out to be 52. How should you think of the mean of the sample? —– According to the table, the score 52 resides outside of the second raw range. That is, your mean is outside of the range in which 95% of means of sample means can be found. In other words, this is a rare extreme case, if you have to believe the manufacturer's claim. In 95 out of 100 cases, the means are supposed to be found in between 52.3 to 55.7. And this case (mean=52) is supposed to be the five out of 100 cases. Therefore, your sample shows that the information which the manufacturer gives us is unlikely true. Maybe the realistic battery life is a bit shorter than that it advertise. You also acknowledge that the chance of your claim to be false (accusing the manufacturer) is about five out of 100 cases. (This means that even though you find the mean of battery life in the sample set is 52, the sample might have been from such a rare case (one of 5 out of 100 cases). Your director will get your report tomorrow morning and send the story to the major media hoping that they will listen to it.

Reference

Weiss, A. J., & Leets, L. L. (1998). Introduction to Statistics for the Social Sciences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.